More From News

UIII Strengthens Its Academic Resources with Read Japan Project

February 25, 2026

January 29, 2026

Prof. Jamhari Makruf, PhD*)

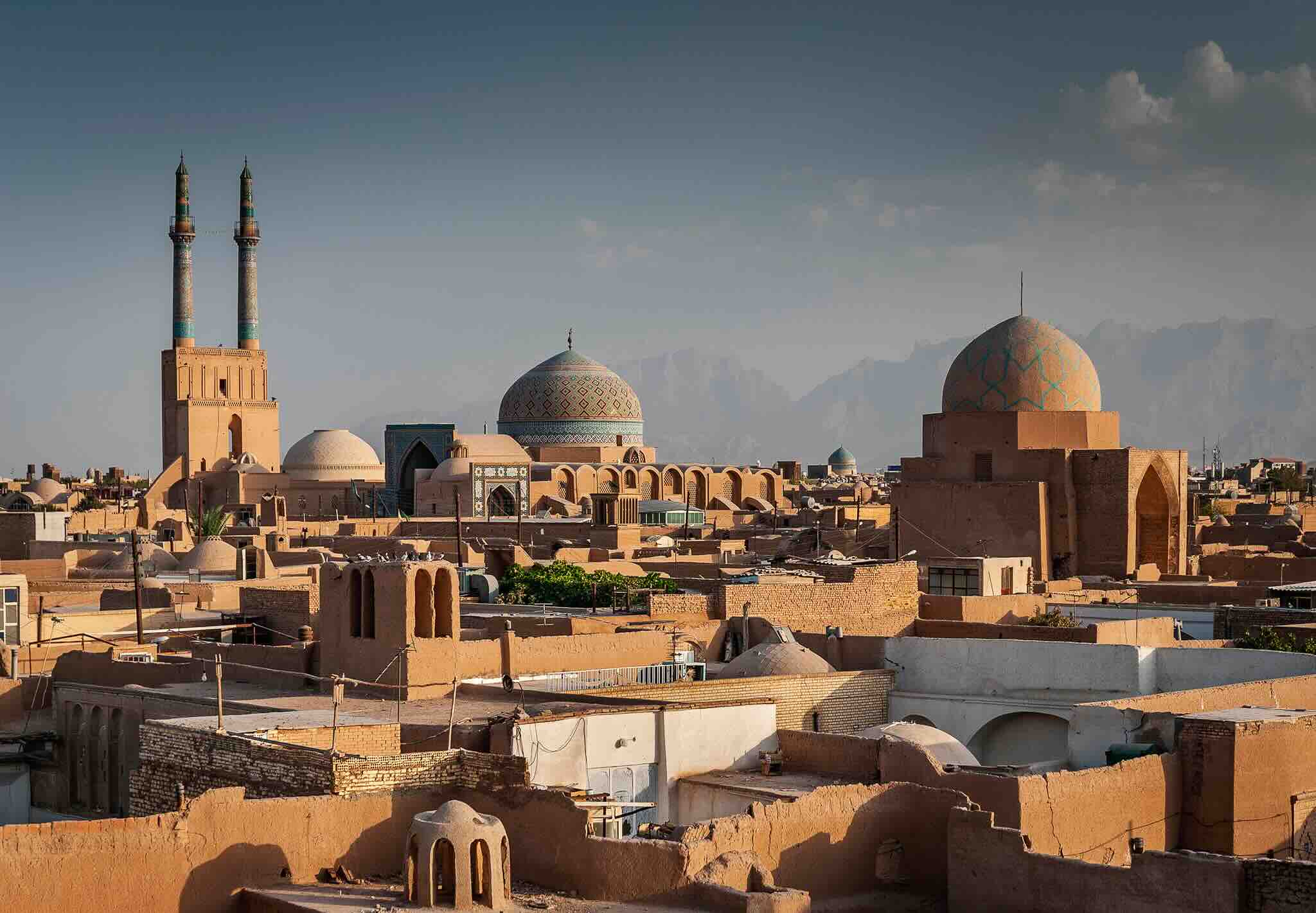

JAKARTA, DISWAY.ID — Let us speak about Iran. In its long history, Iran was once known as Persia.

In 1935, Reza Shah Pahlavi requested that the name “Iran,” meaning the land of the Aryans, be used in international political communication. Since then, Iran has become the official name of the state, replacing Persia in global diplomatic contexts.

Last year (2025), I visited Iran, approximately two weeks before Israel launched an attack targeting an Iranian military figure in Tehran.

Together with participants from various Muslim countries, we attended the commemoration of the death of Ayatullah Imam Khomeini at the Haram Mutthohar, where he is buried.

The event was attended by thousands of Iranian citizens. On that occasion, Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatullah Ali Khamenei, delivered a state address recalling the struggles and aspirations of the Islamic Revolution.

He emphasized the right of the Iranian people to self-determination and to the pursuit of knowledge, including the capability to enrich uranium. The speech was met with religious chants echoing from the audience.

Iran has long attracted global attention. The Cambridge History of Iran (2008) explains that since the pre-Islamic era, the region now known as Iran has been a major center of civilization.

The Persian Empire, beginning with the Achaemenid dynasty in the sixth century BCE, built an expansive realm stretching from Central Asia to Egypt and Greece, making it one of the largest empires in world history.

After the Achaemenids, Persia came under the Parthian and Sassanid dynasties, each exerting significant influence in science, culture, and regional politics.

In the seventh century CE, Islam entered and conquered Persia. This conquest, however, contributed greatly to Islamic civilization. Persian influence became deeply embedded in Islamic literature, architecture, administration, and philosophy.

It is therefore unsurprising that many great Muslim scholars, such as Ibn Sina, Al-Biruni, Al-Khawarizmi, Abu Hanifah, Al-Ghazali, and Suhrawardi, originated from Persian lands or were nurtured within its intellectual traditions.

Modernization and the Iranian Revolution

During the Second World War, Iran again became an arena of great-power rivalry. Britain and the Soviet Union occupied Iran out of concern that it might align with Germany.

Iran’s strategic geography made it a vital logistical corridor for the war effort. From that period onward, Western influence, both European and American, grew increasingly strong in Iranian politics.

Iran entered a phase of large-scale modernization in 1963 through what became known as the White Revolution, initiated by Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi.

This revolution was termed “white” because it was carried out without war. Its programs included industrialization, agrarian reform, women’s rights initiatives, land ownership limitations, and the modernization of major cities.

This modernization generated rapid economic growth. Oil prices surged, state revenues increased, women’s participation in public life became more visible, and urban lifestyles grew increasingly modern.

Yet modernization also provoked sharp criticism. Economic inequality widened, urbanization eroded rural traditions, land reforms harmed small farmers, and secularization was perceived as threatening the religious identity of society. The Shah’s authoritarian and repressive leadership further intensified public dissatisfaction, culminating in the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

The revolution of 1978–1979 shocked the world. Charles Kurzman described the collapse of the Shah’s regime as unthinkable.

The Shah’s regime was powerful, backed by the military and the United States. Yet massive demonstrations against authoritarianism, restrictions on freedom of expression, and excessive dependence on the United States continued to grow.

Modernization that marginalized religion triggered resistance from Shi‘a clerics. Iran is the global center of Shi‘a teachings, home to major religious learning and rituals such as Ashura and Arba‘in.

The Arba‘in pilgrimage, walking from Najaf to Karbala over roughly 80 kilometers, is attended by millions and is estimated to surpass even the number of pilgrims performing the Hajj.

One of the central pillars of Shi‘a doctrine is the concept of Imamah. In this tradition, the Imam is not only a spiritual leader but also a socio-political leader considered infallible.

This concept fosters strong loyalty, solidarity, and obedience among Shi‘a followers, making them a powerful socio-political force.

Post-Revolutionary Iran and Regional Tensions

Intellectual figures such as Ali Shariati, along with leftist socialist groups, also criticized modernization that benefited only the royal elite. Social inequality widened and corruption proliferated. Groups such as Tudeh and Mujahidin-e Khalq organized underground movements.

The convergence of Shi‘a clerics, intellectuals, and leftist movements ultimately brought down the Shah in 1979.

After the revolution, Iran established an Islamic Republic based on the concept of Wilayatul Faqih, in which political and religious authority rests in the hands of the highest-ranking cleric.

This concept generated debate. Some proposed collective clerical leadership to prevent the emergence of a new authoritarianism. Nevertheless, supreme authority was ultimately vested in a single figure.

These differences in vision led to the marginalization of socialist and nationalist groups from government. Iran subsequently developed into a Shi‘a theocratic state.

This dominance generated regional tensions, particularly with Sunni-majority states. The 1987 Hajj riots in Mecca deepened sectarian and geopolitical wounds.

The Iranian Revolution was viewed by some as a victory for Islam, but by others as a victory for Shi‘ism. Since then, various states have supported efforts to contain Iran’s influence.

Monarchical regimes in the region also felt threatened and sought security protection from external powers.

At the Crossroads of the Future

Iran is a land of long civilizational heritage, rich cultural diversity, and abundant natural resources.

Its oil and gas reserves position it as a major global energy player, while its uranium, copper, iron, and gold reserves strengthen its strategic standing in the global geopolitical map.

High-value agricultural products such as saffron, pistachios, dates, and caviar demonstrate that Iran is not merely a land of energy, but also of culture and knowledge.

Its geographic position, at the intersection of West Asia, Central Asia, and global trade routes, makes Iran nearly impossible to ignore in global strategic interests.

At the same time, the strength of the Shi‘a community constitutes the country’s primary socio-political foundation. Loyalty to the concept of Imamah and religious leadership grants Iran significant bargaining power domestically and regionally.

It is difficult to imagine major change in Iran without the involvement of Shi‘a leadership, for moral and political legitimacy are deeply rooted there.

Recurring large-scale demonstrations show that the support or opposition of the Shi‘a population can determine the direction of national stability.

The future challenge lies in how Iran, with its system of Wilayatul Faqih and strong social backing, can build sustainable prosperity and peace.

Economic sanctions undoubtedly constrain maneuverability, yet Iran’s achievements in health, technology, agriculture, and even strategic sciences demonstrate notable resilience.

However, recurring external conflicts risk draining national energy and delaying welfare agendas. At the same time, the international community is also called upon to adopt a more just and consistent approach in engaging Iran as part of the global order.

The question remains: will Iran be able to transform its ideological strength and natural resources into pathways toward peace and prosperity, or will it remain trapped in an unending vortex of conflict?

*)

Rector of Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia

This article has been previously published here:

Universitas Islam Internasional Indonesia